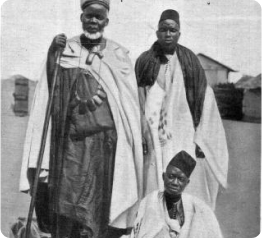

Al-Hajj Umar Al-Futi Tal

By Zakariya Wright

Shaykh al-Hajj Umar b. Sa’id al-Futi al-Turi (1796-1864), commonly known as Hajj Umar Tal, was perhaps the most famous of all Tijani figures in the nineteenth century. He was an accomplished scholar, author and social activist. He combined the greater holy war (jihad al-akbar) against the ego-self (nafs) with the lesser war of arms (jihad al-asghar) in the hope of establishing a Muslim empire of justice and peace in West Africa. His magnum opus, the Kitab rimah hizb al-rahim ‘ala nuhur hizb al-rajim (“The book of the lances of the league of (Allah) the Merciful against the necks of the league of (Satan) the accursed”), is considered a “veritable compendium” and one of the most important works of the nineteenth century anywhere in the Muslim world (Hunwick, 1992). The work is normally printed with the major work of the Tijaniyya, the Jawahir al-Ma’ani. The “Umarian” state al-Hajj Umar had forged by 1860, although short-lived, was one of the largest ever seen in West Africa. His legacy of resistance to French colonial conquest has inspired West Africans from all walks of life to the present time.

Al-Hajj Umar was born in Helwar, Futa Toro, in present-day northern Senegal. He hailed from the noble Fulani, a people who had become renowned for their Islamic scholarship throughout West Africa by the seventeenth century. His father Cerno Saidu (Arabic, Sa’id) studied at the famous Islamic university of Pir Sanikhor in Senegal. Saidu lived the life of a simple farmer, devoting himself to studies and worship rather than participate in the Fulani jihad of Abd al-Qadir Kane in 1776. A touching story is related in an oral tradition collected by Madina Ly-Tall (1991) of al-Hajj Umar’s respect for his father. Once, Umar’s beloved son, Muhammad Makki, told his father in jest, “My father was better than yours.”

Al-Hajj Umar said, “What you say demands proof.”

“My proof is that Shaykh Umar is my father,” said Muhammad Makki. “And he is the most knowledgeable among both black and white; he went to Mecca; he engaged in jihad; and he is the khalifa of the Tijaniyya. These are my proofs: your father did not have any of this.”

Umar responded, “It is my turn to present my proofs. My father was named Cerno Saidu, he taught all sorts of sciences to his disciples. He had a field in Barol Talbe. To go there he veiled his face to not envy the fields of others. When he came to his field, he put himself to work farming, all the while reciting the Qur’an. At the time of prayer, he prayed. He used to go hunting, and my mother would prepare dinner with what he brought home. This is what he would eat. He had (sons) Elimaan Ibrahima, who is a saint; Tapsiru Autumani, who is a saint; Alfa Ahmadu, who is a saint; Cerno Bubakar, who is a saint; Alfa Usman, who is a saint; El Hadj Aliu, who is a saint; and me. We must wait to see if your father will have such sons. And the son is only the reflection of his father’s character.”

Al-Hajj Umar then added, “Do not forget that your father has killed people, has devastated fields, has dethroned kings. He will have to make an accounting before Allah for these things. As for me, my father has not done any of this, he was a simple farmer. There are my proofs” (Ly-Tall, interview with Tapsiru Ahmadu Abdul Niangan, 1981).

Soxna Adama Aise, the mother of al-Hajj Umar, likewise had a great reputation for piety. She was a niece of the famous Qadiri scholar and jihadist Sulayman Bal. It is related that a torrential downpour occasioned the birth of Umar, threatening to drench mother and child since the roof of the house was being repaired. While everybody else in the family became soaking wet, Soxna Adama and her son remained dry. Once some dignitaries of Masina (Mali), impressed with the scholarly piety of al-Hajj Umar, queried him about his family, asking him if such attributes were common among his father’s people. He replied that many in his country (Futa Toro) were of a similar spiritual stature to his father, but that “a woman comparable to my mother, I have not left in my country and I assure you there is neither such a woman in yours” (Ly-Tall, 1991).

Al-Hajj Umar was a precocious student of the Islamic sciences, memorizing the Qur’an with his father at a young age. He was next trained to be a Qur’an school master by his elder brother Alfa Ahmadu, until he began traveling in search of knowledge. By this time, it is said he had developed a keen interest in books and poetry detailing the life and character of the Prophet Muhammad. He would later say:

Allah, from His bounty, endowed me with the love for His Prophet. (From an early age) I was confounded with love for him, a love permeating my interior and exterior; something which I both hid and manifested in my soul, my flesh, my blood, my bones, my veins, my skin, my tongue, my hair, my limbs, and every single part making up my being. And I praise Him on account of this. (Safinat al-Saada; cited in Ly-Tall, 1991).

Umar studied under many of the renowned teachers in Futa Toro of his day, such as Cerno Lamin Saxo, Amar Saydi, Yero Buso and Horefonde. He excelled in the study of jurisprudence (fiqh), and even after his establishment as a Sufi shaykh, scholars used to visit him in Dingiray to discuss with him points of jurisprudence. His studies in Futa inevitably led him to the famous school of Pir Sanikhor, where his teacher, Serin Demba Fal, observed in him exceptional scholastic ability. His first stay outside of Futa in search of knowledge was in the Mauritanian town of Tagant, where he would have been exposed to the Tijaniyya (although it is not believed he took the Tariqa at this time). On his return from Mauritania, he was already known as a learned teacher of the Islamic sciences. During a second visit to Mauritania, or perhaps during a visit to Futa Jallon (present-day Guinea), Umar was initiated into the Tariqa Tijaniyya by Abd al-Karim al-Naqil, a student of Mawlud Fal. The two became close companions, and traveled together to Futa Jallon where Umar spent years in the company of Abd al-Karim, learning from him the remembrances of the order and some secrets such as the prayer hizb al-sayf.

Soon after the death of Abd al-Karim, Umar set off with his family to accomplish the pilgrimage to Mecca. He arrived in 1827 and soon became acquainted with the prominent student of Shaykh Ahmad Tijani, Sidi Muhammad al-Ghali. Al-Hajj Umar became Sidi al-Ghali’s closest disciple, and al-Ghali gave him full investiture in the Tariqa following a vision of Shaykh Ahmad Tijani in the Prophet’s mosque in Medina, where Shaykh Tijani told al-Ghali, “I have given Shaykh Umar ibn Sa’id all that he needs in this Tariqa in the way of litanies and secrets. You have only to inform him of the details.” Sidi al-Ghali thus gave Hajj Umar the status of khalifa in the Tariqa. Where Hajj Umar describes the degree of the muqaddam (propagator) as someone commissioned by the Shaykh to “teach the obligatory remembrances as well as some of the remembrances peculiar to the elite,” he describes the position of khalifa as the manifestation of the Shaykh (Tijani) himself:

“He is a representative of the Shaykh without restriction. The muqaddams and their students are therefore included among the subjects of the khalifa. Obedience to the khalifa is incumbent upon them […] Someone who is taught by the khalifa is on equal footing with someone who is taught by any other, because of the degree of deputyship” (Rimah Hizb al-Rahim).

Before leaving the company of Sidi al-Ghali in 1830, al-Ghali confirmed his status as khalifa for West Africa and told him to “clean the lands of the stench of paganism.” While in the Middle East, al-Hajj Umar also visited Jerusalem, Syria and Egypt, where his reputation for piety and learning were recognized. It is said he led the prayer in the Dome of the Rock (Jerusalem), cured the son of a sultan from madness in Syria, and astonished scholars in Cairo by his vast erudition (Ly-Tall, 1991; Ba, 1990).

Al-Hajj Umar returned from the Middle East by way of Sokoto in modern day Nigeria, (which he had also visited on the way to the Hijaz), arriving in 1831-2. He was accorded a grand reception by Sultan Muhammad Bello, the son of Shehu Usman dan Fodio. There is no evidence that Sultan Bello actually took the Tariqa Tijaniyya, but it is undeniable the two were the best of friends. Bello gave Shaykh Umar his daughter Maryam in marriage, and Umar accompanied Bello on various military campaigns. Bello relied on the Shaykh for guidance through his istikhara (prayer for guidance) and to pray for rain in times of draught. Hajj Umar had great respect for Muhammad Bello and the Usmani tradition. In the Rimah, Umar speaks of the Sultan Bello as “the equitable imam, the scholar who puts his knowledge into practice, the excellent saint, the commander of the faithful, Muhammad Bello.” Musa Kamara cites a letter from Sultan Bello to the inhabitants of Futa Toro on behalf of Shaykh Umar likewise attesting to his love for the Shaykh: “We consider his departure (from Sokoto) like a death that infiltrates our blood, as we are losing a great friend” (Kamara, 1975).

In his Rimah, Shaykh Umar recorded an incident of some significance in unraveling the connection between the Sultan and the Shaykh. Some have of course claimed the Bello was in fact initiated into the Tijaniyya by Umar, but neither Bello nor Umar provide evidence of this. Nonetheless, the following passage from the Rimah demonstrates Bello’s profound respect for the Tijaniyya. Shaykh Umar cites here a dream Bello had on the 14th of Rabi al-Awal in the year 1251 A.H. which he had recorded and given to the Shaykh in writing:

“I saw in the state of sleep … that the Hidden Pole (al-Qutb al-Maktum), the Sealed Isthmus (al-barzakh al-mukhtum), the Seal of the Saints, Shaykh al-Tijani (may Allah be pleased with him and us on his account), had come to our land and rallied the people to him. When I reached him, I found in his presence the fortunate and successful Sayyid ‘Umar b. Sa’id as his lieutenant. The Shaykh was telling him, “The people of this country will not derive benefit from any (new) knowledge in addition to their (present) knowledge.” I (Bello) said to the Shaykh, after greeting him with the salutation of peace, “You should know that I am one of those who love you, and this only for the sake of Allah Most High, out of Divine command, not for any worldly cause or reason, praise be to Allah. I have noticed the mention of the Seal of Saints among the discourses of the elite.” He said, “You knew or saw his remembrance in the origins (lawaqih) of the lights.” Then I said, “I have heard from our Shaykh (Usman dan Fodio) that he met with you (Shaykh Tijani) next to his house in Degel … I want your assurance that as I am seeing you here now, I will see you in Paradise,” and I repeated these words three times with all my spiritual zeal (himma) … Then he sent me in search of some radish seed powder for some medicine, so I went in search of it, then I recovered consciousness.”

Al-Hajj Umar relates then that when Sultan Bello came to tell him of the dream, he filled a large vessel with radish seed, brought it to him, and said, “Take what your Shaykh instructed me to bring him, for you are his khalifa and his representative (na’ib).”

Shaykh Umar left Sokoto following the death of Sultan Bello (1837), but it is likely he was delayed on account of the failing health of his wife Maryam (d. 1838). In any case, there is record of him cooperating with the new Sultan, ‘Atiq, and marrying another wife from Sokoto, this time a daughter (Aisha) of Cerno Muhammad Nema, a judge (qadi) appointed by Shehu Usman. It seems Shaykh Umar considered both of his wives from Sokoto to be saints (Ly-Tall, 1991), and he relates some of their visionary experiences in the Rimah.

After traveling widely throughout West Africa – such as Masina (Mali), Sine-Saloum (Senegambia) and Futa Toro, Shaykh Umar settled in Futa Jallon, eventually founding the town of Dingiray. In Futa Jallon, Shaykh Umar spent ten years teaching his growing numbers of disciples. He was especially renowned for his teaching of jurisprudence, hadith and, of course, Sufism. Many of the region’s oppressed and downtrodden found refuge in his settlement, as did scholars from all over West Africa. Resenting his growing influence, the non-Muslim leaders in the area attacked his settlement in 1851. Nearly a year later, Shaykh Umar received official permission for the jihad from the Prophet Muhammad and Shaykh Ahmad Tijani in a visionary encounter. The jihad was first exclusively directed against the non-Muslim Bambara, whom al-Hajj Umar accused of grave injustices, enslaving Muslims and threatening the practice of Islam.

When he conquered the Bambara city of Segu in 1961, he found evidence of an alliance against him between the Bambara kingdom and the Muslim state of Masina. His resultant jihad against Masina, whose capital Hamdullahi he captured in 1864, touched off a virulent polemic between the supporters of al-Hajj Umar and the supporters of Masina, the latter which included the scholars of Timbuktu (Mahibou and Triaud, 1983). By 1854, Shaykh Umar’s mobilization of Futa Toro led to direct conflict with advancing French commercial and military hegemony. Besieged on two fronts, Shaykh Umar died in battle in 1864 near Hamdulillahi. His empire was held together by his son Ahmad until being dismantled by the French some twenty years after the Shaykh’s death.

The literature on Shaykh Umar remains mostly preoccupied with his political and social revolution in West Africa. This is understandable, given

the widespread impact of his political activities. But his scholarly legacy has far outlasted any temporary political role he endured. His descendent Seydou Nourou Tall became a key Muslim and Tijani figure in twentieth century West Africa and was appointed as a supreme religious leader of West Africa by the French. Later Tijani scholars in West Africa, such as Al-Hajj Abdoulaye Niasse and al-Hajj Malik Sy, both had important initiations into the Tijaniyya through students of al-Hajj Umar. Shaykh Umar’s book, the Rimah, remains one of the mostly widely read books of the Tijaniyya order.

Works cited

-Shaykh Umar b. Sa’id, Rimah hizb al-Rahim ‘ala nuhur hizb al-rajim.

-Madina Ly-Tall, Un Islam Militant en Afrique de l’Ouest au XIXe Siècle: La Tijaniyya de Saiku Umar Futiyu contre les Pouvoirs traditionnels et la Puissance coloniale (Paris, 1991).

-Ahmadu Hampate Ba, “Sheik Ahmadu and Masina,” and Mohammadon Alion Tyam, “The Life of al-Hajj Umar,” in Colins (ed.), Western African History: Texts and Readings (New York, 1990).

-Cheikh Moussa Kamara, La Vie d’El Hadji Omar (translated from Arabic by Amar Samb, Dakar, 1975).

-John Hunwick, “An Introduction to the Tijani Path,” in Islam et Societés au Sud du Sahara (1992).